By Alonso Aguilar

Although many classic films from the “Global South” are pigeonholed according to their political relevance, their virtues go well beyond these initial categorizations. Their palpable sense of urgency is amplified by daring riffs on the traditions they openly opposed, re-contextualizing them with nuanced portrayals and outrageous stylistic mashups that leave their qualification as “radical works” somewhat short of showcasing their true scopes.

In recent memory, the success of Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Cinema Novo love letter Bacurau (2019) has helped to spark some retrospective interest in the weirder inclinations of Brazil’s national filmography, like Glauber Rocha’s acid forays into Western territory, for example. Unfortunately, such instances are few and far between for most Latin American filmographies due to a general lack of accessibility that makes many essential features remain unfairly buried in relation to contemporary cinematic discussions.

One of the most glaring omissions has been the legendary Cuban film Lucía (1968) by director Humberto Solás, widely considered one of the best Latin American films ever made. No study of the Third Cinema movement, Cuban filmic history, or even Latin American cinema can be complete without a reference to such a foundational piece, and yet, apart from some limited screenings following its 2017 restoration, it had not been accessible for decades and was virtually unseen. Released by The Criterion Collection just last week, this shall no longer be the case.

Fifty-two years might have passed since its original release in Cuba (and forty-six after its short US opening), but the concerns put forward by Humberto Solás’ masterpiece remain as relevant as ever.

Structured as an operatic retelling of Cuban history, Lucía frames the struggles of three different women with the same name during three different eras. The role of each one of them showcases the distinct contradictions of each period, as well as the underlying threads of patriarchal menace and socioeconomic inequity. In Solás’ own words: “Lucía is not a film about women, but a film about society”.

The first part of this tryptic is set during the 1895 war between the Spanish guerrilla and the Cuban mambises, and carefully constructs an effective costume romance focusing on Lucía (Raquel Revuelta), an aristocratic woman from Havana, and her impossible love affair with a Spanish official. The ornate camera movements and aura of bourgeois disillusionment turns more and more hectic as the central romance is progressively overshadowed (both literally and symbolically) by the threat of a violent anti-colonial uproar.

Almost forty years later, during the final days of the Machado regime in the early 1930s, the second Lucía (Eslinda Nuñez), the disenchanted daughter of a high-class family, seeks to become an active agent in the opposition and begins to fall for a young and idealistic revolutionary.

As Solás engages with the complex psychology of his female protagonists, the shift between segments goes well beyond just setting and character motivations: the whole world feels different. The crumbling ivory tower of Colonial high-society inhabited by the first Lucía was perfectly depicted as an exuberant neorealist melodrama, and accordingly, the guerrilla setups and precocious intellectual discussions inherent to the everyday life of the second Lucía are portrayed through the dreamy lens of a love story in a nouvelle vague style.

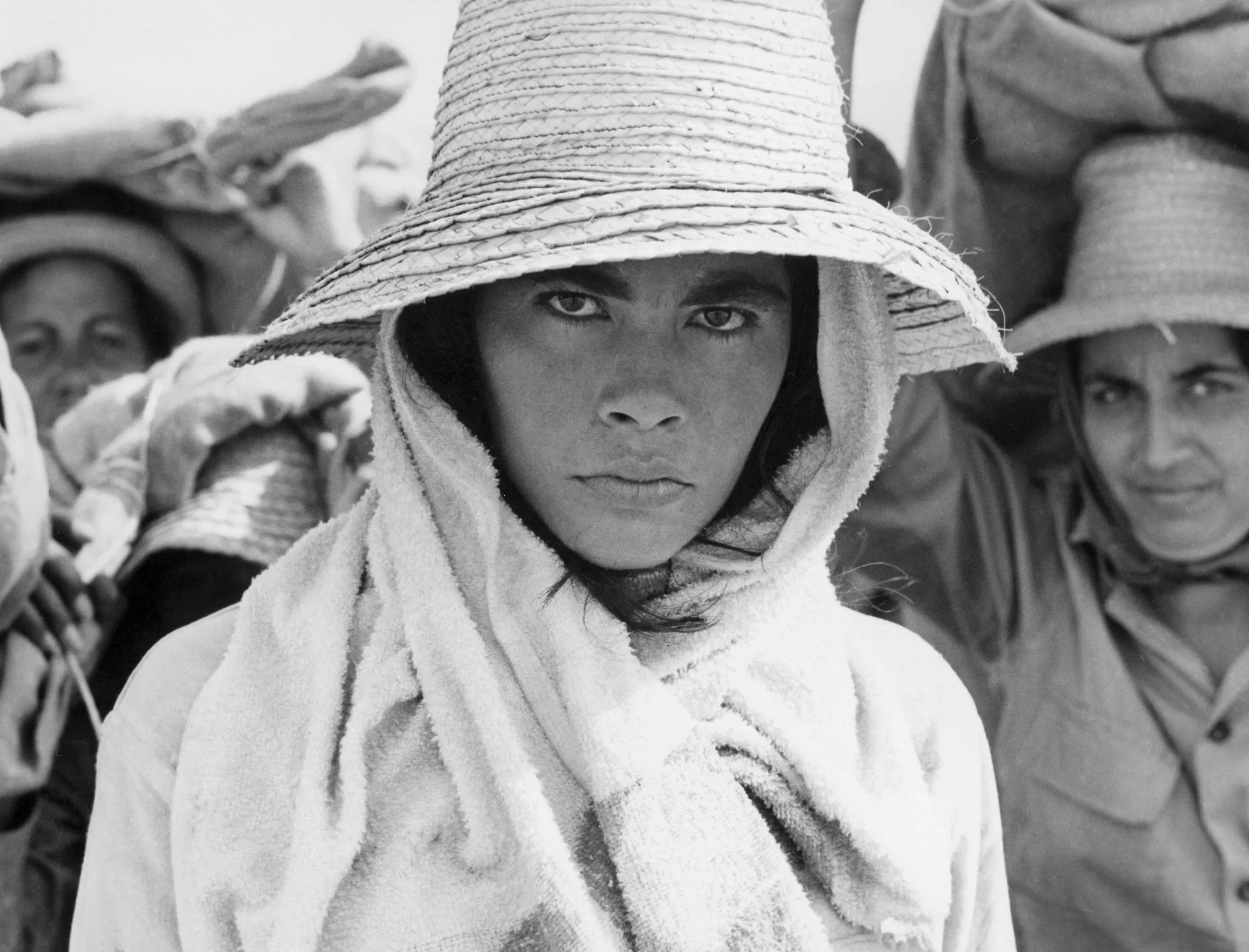

The same goes for the last Lucía (Adela Legrá), a peasant factory worker who struggles constantly with the toxic masculinity of her truck driver boyfriend during the dawn of Castro’s Cuba. Narratively, this last story is aligned with the tropes of social realist films, but Solás makes it his own by incorporating the satirical sense of comedy featured in the post-revolutionary slapsticks of his countryman Tomás Gutierrez Alea (The Death of a Bureaucrat / La muerte de un burócrata).

The many styles at play in Lucía overlap and contrast each other in clever ways, all while managing to feel cohesive thanks to Solás’ overarching use of expressionistic editing and free-flowing camera movements.

Without glossing over the nuances of the island’s tumultuous historical process, the film addresses hardships of universal consequence. The three titular women experience different shades of oppression depending on their social standing and specific moment in time, but they nevertheless all understand themselves as suffocated by political circumstances that limit the extent of their desires. The ever-present promise of liberation might change discourse and color, yet the chains of the patriarchy are not easily shaken. To that, in the most lasting and powerful aspect of its legacy, Lucía has the conviction to never settle.

Lucía was recently released on Blu-Ray as part of the Criterion Collection’s Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Project No. 3, and can also be watched on The Criterion Channel streaming platform.

______________

Alonso Aguilar is a cultural journalist from San José, Costa Rica. He does editorial labor in Krinégrafo: Cine y Crítica and his writings have featured in Mubi Notebook, Bandcamp Daily, Film International, photogénie, Cinema Year Zero, Costa Rica Festival Internacional de Cine, La Nación and Revista Correspondencias.