By Oscar Molina*

In 1977, at the age of 22, American Paul Bardwell arrived in Medellín as an English teacher. Three years later, the native of Hatfield, Massachusetts was already acting as general director of the city's Centro Colombo Americano, a binational center like those found in many parts of the world with the mission of promoting the teaching of English and North American culture. It was at that time, and for the rest of the 1980s, that Medellín was considered the cocaine capital and the most violent city in the world.

Bardwell generated meeting spaces for audiences, creators, critics and managers around film, visual arts, books, music and even dance and gastronomy. The people of Medellín, who have prided themselves on being part of a conservative, dogmatic and astute “race,” found themselves interacting systematically with ideas that questioned, works that questioned and people who challenged these standards.

With Bardwell, artists, academics, exhibitions, shows and concerts soon arrived from the United States and later from other latitudes to Medellín, a city that was outside the agendas and itineraries of many creators or their promoters.

Many of these meetings took place outside the walls of the Colombo Americano and were organized in conjunction with other cultural centers, universities and local, national and international institutions, which made evident its spirit to integrate strengths and build a cultural project for the city and not only for its organization.

This process of circulation also occurred in two directions. Bardwell deployed his management capacity to circulate the work of local and national artists in spaces in the United States and other countries, a process of recognition of the talent and quality of the artistic production that has been made in the country, and the need for this production to establish a dialogue with audiences in a wider geography.

In 1987, drug trafficking violence made Colombo Americano a military target: 40 kilos of dynamite destroyed 60% of its facilities. The day after this terrorist act, Bardwell began reconstruction and three weeks later reopened the facilities. In 1989, in the ruins left by the violence, Bardwell expanded the library facilities, transformed the gallery into a space for contemporary art, and inaugurated a movie theater, with a quality of projection and sound superior to what the city had to offer. But more than with infrastructure, he responded to the violence by expanding the cultural offerings beyond the mission of a binational center with works and artists of diverse origins.

The Colombo, as the people of the city affectionately call it, became a cultural center to promote multiculturalism and the avant-garde, principles that, in Paul's own words, guided his work as a strategy to foster respect and tolerance.

The movie theater was the beginning of the most ambitious program for the development of film audiences in the country. It quickly became a great referent for the organization and exhibition of specialized cycles and exhibitions from different countries; workshops and films of scarce circulation. In 1990, it published a booklet of photocopies with information that expanded the synopses of the films on the billboard.

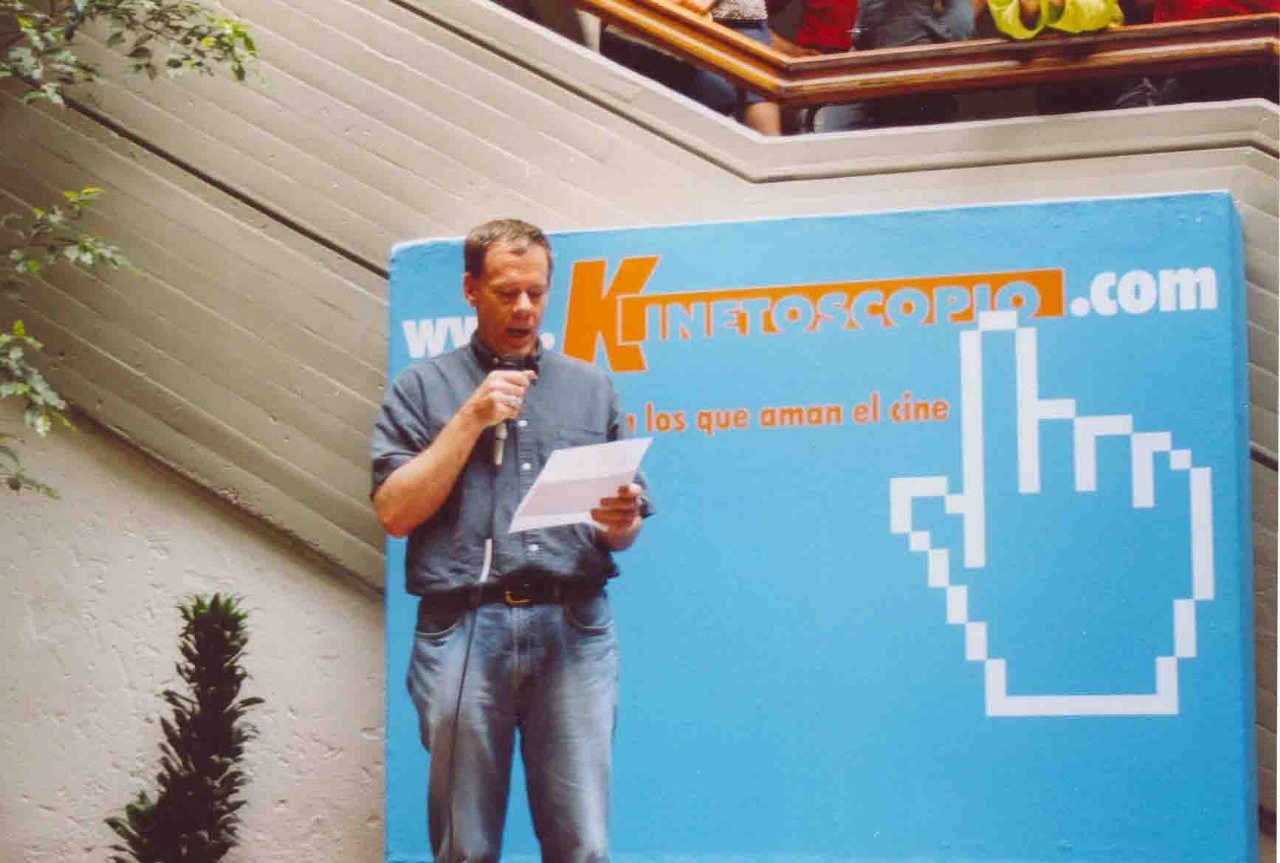

This would be the beginning of Kinetoscopio, a magazine that became the longest-running cultural publication in Colombia and, for many years, the only one specialized in cinema; home to the most renowned film critics in the country and some in Latin America, and cradle of many new critics who continue this work to this day.

It also made available to the public a video library with a wide range of content, both of referential works from the history of cinema and contemporary films, to which it was difficult to find in the country. In 1999 it opened a second movie theater and in 2000 a documentation center specialized in cinema and the arts. Parallel to the promotion of this cinephilia and spaces for reflection on cinema, the Colombo also offered courses and workshops to promote local and national audiovisual production.

In recent years, the quality and quantity of film production in Colombia has increased significantly. It is not by chance that some of the most outstanding productions originate in Medellín, heirs in part of this film culture.

The public's response to the offerings of this cultural center was enthusiastic. The usual thing was to see long lines to enter the movie theaters, full theaters, congestion of people in the corridors contemplating the visual arts exhibitions that overflowed the space of the Gallery, spontaneous or planned meetings at the entrance of its facilities or in the cafeteria. Going to the Colombo was a motivation to return to the city center, which had lost the glamour of other times.

Bardwell was not someone who sought notoriety or the limelight. He was an observant person, with few words and simple speeches. He was often present at the activities he organized or supported as a spectator. His dedicated work consisted of connecting people and institutions, supporting experts to carry out their work, managing resources and promoting spaces for working groups to meet.

In the last years of his life he led initiatives that promoted the rights or talents of specific populations. In 2001, together with the Cinemateca de Bogotá and the Goethe Institute, he started a film series with LGTBI content that the following year would become the Ciclo Rosa, the film festival with the greatest impact in the country to circulate and discuss content on diverse sexualities.

It also supported the contemporary African dance group ‘Sankofa’, generating training processes with dancers from Burkina Faso. The Library's existing music collection was nourished with a wide and dedicated selection of African music and music from other geographical origins. And as an act of revelation and geopolitical recomposition, it led and supported the exchange of artists between countries of the "global south" with the purpose of allowing dialogue and recognition of forms and ways that are not necessarily part of the agendas of the countries of the "global north".

Bardwell's early death in 2004 at the age of 49 left a city transformed and inspired by his cultural project. His departure coincides with a moment of openness and consolidation of other cultural projects, which in some way take up initiatives addressed by Paul, and a city more receptive to interacting with more diverse people.

For many, the success of Bardwell’s management has to do with his U.S. origin, being a white man, and having had this binational center as a platform for action. In part, that is true. But we can see around us people who have had privileges that do not display a commitment to their environment beyond their institutional mission.

Today the city, the country and the world face different challenges than in Bardwell's time at Colombo. Perhaps we have more cultural organizations and projects. However, there is anxiety due to radicalizing discourses, violence that does not cease and expands, and the certainty that our way of life could lead us to extinction. What cultural project can Bardwell’s spirit suggest for our times? Twenty years after his death there is much to learn from the spirit of this gringo who led one of the most audacious cultural projects in Colombia and Latin America.

Oscar Molina is a filmmaker, director and producer of La Casa de Mama Icha. He was director of the Film Program at the Centro Colombo Americano in Medellín, as well as editor and director of Kinetoscopio magazine between August 2004 and December 2006.