By Natalia Hernández Moreno*

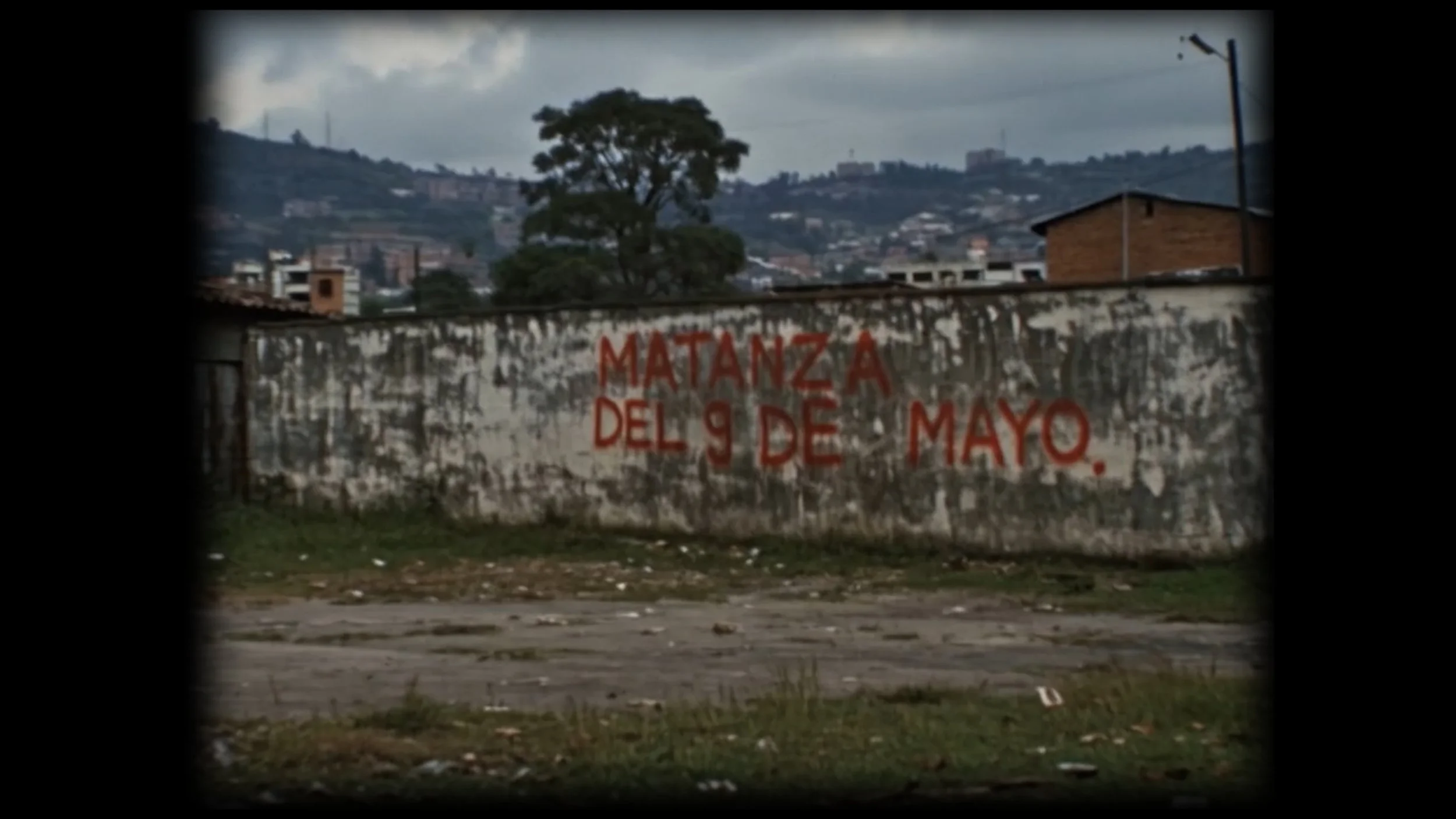

A deteriorated celluloid reel, purportedly recovered from 1982, flickers with a succession of quotidian scenes, among which a few fragments appear to testify to violent events that took place on May 9 of that year—until it doesn't. In 09/05/1982, Colombian filmmakers Jorge Caballero (Paciente) and Camilo Restrepo (Los Conductos) present a succession of quotidian scenes that slowly reveal fragments of a violent, fictionalized tragedy. Produced by Artefacto, the film arrived at the 63rd New York Film Festival’s Currents program last September as a formally daring provocation probing the fragility of historical memory and the ways in which images are mobilized to shape it.

Though it mimics the texture of a recovered historical document, 09/05/1982 is a work of "synthetic footage." It is a film that weaponizes the very tools of our current anxiety—Artificial Intelligence—to interrogate the historical weaponization of images. By pairing fabricated visuals with the authoritative cadence of a narrator, Caballero and Restrepo expose the structural mechanisms by which memory is manufactured, manipulated, and eventually erased.

I sat down with Jorge Caballero to discuss the dual origin of this project, the difficult translation from optical recording to textual code, and why, in an era of deepfakes and digital flooding, a "dishonest" film might be the most honest way to safeguard the archival question.

How did the theoretical framework of the “synthetic footage film” emerge? And how did the idea of opposing it to the tradition of found footage come about?

This project and its research have a dual origin. On one hand, there is a practical side: Camilo [Restrepo] is at a point where he is studying what it means to work with filmic materials and exploring their limits. I don’t want to get too far ahead of what he might say, but the idea stems from there—from the notion of making a film to distance himself slightly from physical material, but without sacrificing what working with physical material entailed for him. That is to say: a particular texture, a particular visuality.

On the other hand, for some time now, I have been reflecting on the logic of what creation with Artificial Intelligence means. We found an interesting point of connection there that pointed toward a straightforward question: What would happen if we made a film or a record that started from the complexity of what a "synthetic archive" means? And where do we situate this generated synthetic archive?

I’m interested in how the montage worked, from the most obvious question regarding the "how-to" to the language of coding. How did you both approach translating an idea into code and then cuarting and assembling those fragments?

That is fascinating. Working with Artificial Intelligence is complex because it requires a pedagogy that people often fail to understand: the need to translate text—or other concepts that do not originate from an optical apparatus—into something that will ultimately be visual.

In other words, if I have a camera, the device functions as an optical medium par excellence, where I use a lens and that lens allows me to record a process of reality (whatever that may be). Current AI models, especially the versions available when we were conceptualizing the film, are heavily based on textual logic. Therefore, beginning to think in terms of textual logics that could replace, supplement, or complement optical logic is a highly complex task because it will always remain very limiting. It is not the same thing to pick up a camera to film a bird in a tree as it is to write: “I want a medium shot of a bird in a tree.”

There is a translation that is not immediate and must be performed. All this current fear surrounding AI replacing us—which is very understandable—assumes that AI work is automatic and requires no preparation. But the truth is that those with an extensive audiovisual background, as is Camilo’s case, have an excellent facility for describing images because they have created them so many times.

The methodology is quite simple. What we did was a text-to-image workflow, then image-to-video, while the entire sound layer was constructed in a very analog way. That is, we had a written script that was then voiced (one part with AI, but more as a technical mechanism than a creative one).

What happens with AI is very curious because the accelerated generation of images and videos allows you to iterate very quickly on ideas, which is closely linked to your first question about the particularity of the limits of physical materials. If you work with film stock, processing the material is long and complex; naturally, the iteration process is more difficult.

That was certainly not our case. In the AI realm, you output a video that triggers a million other videos, creating an incredibly complex curatorial task. The question is how to select 500 possibilities out of a million, and then keep only one.

It’s great that we are moving toward the curatorial gesture, because something that really strikes me about your montage is the emphasis on “accidental” or “collateral” marks of a damaged archive—of material that you want to highlight as mistreated. After selecting the AI-produced images, can you expand on that artisanal interest in accentuating filmic precarity?

There were two primary motivations besides experimentation. The first was understanding that the "trickery" (trucaje) of images—now that we are talking about the relationship between AI and deception—is something rooted in the very origins of cinema. We really liked the idea of trickery as a magical experimentation with images, something very much like Segundo de Chomón or Méliès. That is one vector: the logic of surprise, of magic, of how images are capable of taking us into absolutely fantastic realms.

The other vector was linked to reality, to the logic of the document. That tension between three things that are paramount for us: the material, the archive, and the fact. When you think of a film in Super8 or VHS, there is a logic to those materials that already links you to an archive, even to an era. And that, in a way, gives you a vector of similarity with the "fact"—the ability to assert with certainty that “it happened this way.” In this sense, there was something AI could not entirely provide: precisely that kind of conjunction between film material, archive, and fact.

Those types of things—noise, for example—were elements we felt we had to include to ground further that triad so that our logic of deception could put reality under tension. I think we achieved that with the "tails" (colitas), the 16mm, the scratches on the negative, but above all with the audio—with that natural and simultaneously "broken" sound (all sourced from Camilo’s previous films). We wanted that audio texture to once again call into question the idea that these materials could have been real.

Now that we are in a more sonic environment, can you expand on the voiceover, which was created partly through analog means and partly through AI?

From the script stage, there was an apparent premise of fragmented vignettes and a fragmented voiceover. The premise was: “These are unfinished materials that someone recorded.”

AI is socially associated with the creation of spectacular, impossible, and implausible images. We wanted to ask ourselves what would happen with those "ugly," basic images with poor visual composition; we wondered if the machine was capable of creating banal images filmed from a place of total everydayness. It was difficult because it meant giving the machine the challenge of generating materials that, in addition to being "real," were so "irrelevant" that they had been forgotten.

Something similar happened with the voice and the soundtrack: we had a script with a fragmented logic, which was written by hand, but the person whose voice we liked could not record all the content. So, we decided to train a model so that, with that person’s permission, this artificial voice could memorize the human tone we liked and generate all the material we needed. I believe that through the training of the voice, we managed to give it that "official" (oficialista) tone it has—like a "repentant president."

It’s interesting because there is something involving the technical process of AI that simultaneously serves as an artistic resource. And in the voice, there was a clear technical interest.

How has the film’s reception been? It had its US premiere in the Currents section of the New York Film Festival this year, but it first played for audiences at FIDMarseille and TIFF. I’m curious to know how these different audiences have approached the short, particularly whether there has been a blunt rejection of these technologies in cinema.

It has been particularly gratifying because when this conjunction of AI and cinema is proposed, there is often significant reticence. Understandable, of course. I am very critical of the use of AI in audiovisual media because of the possibilities it offers, the way it floods content, and the issues of bias. I am very aware of that. Consequently, in most cases, I went in very prepared for the initial encounter with the film to be one of rejection. But curiously, it hasn't been that way; it has sparked enriching conversations like this one, about the limits of the archive and what can be achieved.

Above all, it has been this way because, in its dishonesty, it is a film that is honest: it reveals the logic of having been constructed this way. It is not a film that allows doubt to arise in the spectator as to whether they were deceived or not (because the film itself says so). The film resolves its own process. The most gratifying part has been seeing the number of questions it generates regarding its construction process and its ethical limits.

I’d like to close with that idea of the "open question" the film leaves behind. For you, in particular, after this exercise, how do you see the incorporation of these kinds of experiments into your practice? How do you approach these increasingly complex questions?

We are actually starting to conduct workshops on AI and the archive centered around this question of materials. I have been working with the limits of AI for many years now, so this type of experimentation and memory construction isn't particularly novel to me. But what is new with 09/05/1982 is the questions it has sparked about how we, as a society, will coexist with these types of images.

I feel three classes of images are going to permeate our entire visual landscape and imaginary (imaginario): images intended to deceive, images that deceive unintentionally, and images that still belong to the "photographic regime." The coexistence of such a diverse ecosystem of images makes the reading of those images very complex, and it places you, as a spectator, in a challenging position.

Precisely that puts me in the position of researching further and keeping the debate open regarding the construction of memory, the construction of narrative, and, above all, the archive.

This interview has been translated from Spanish and has been edited for length and clarity.

*Natalia Hernández Moreno is Researcher and Outreach Director at Cinema Tropical and a frequent collaborator with TropicalFRONT.