By: Natalia Hernández Moreno*

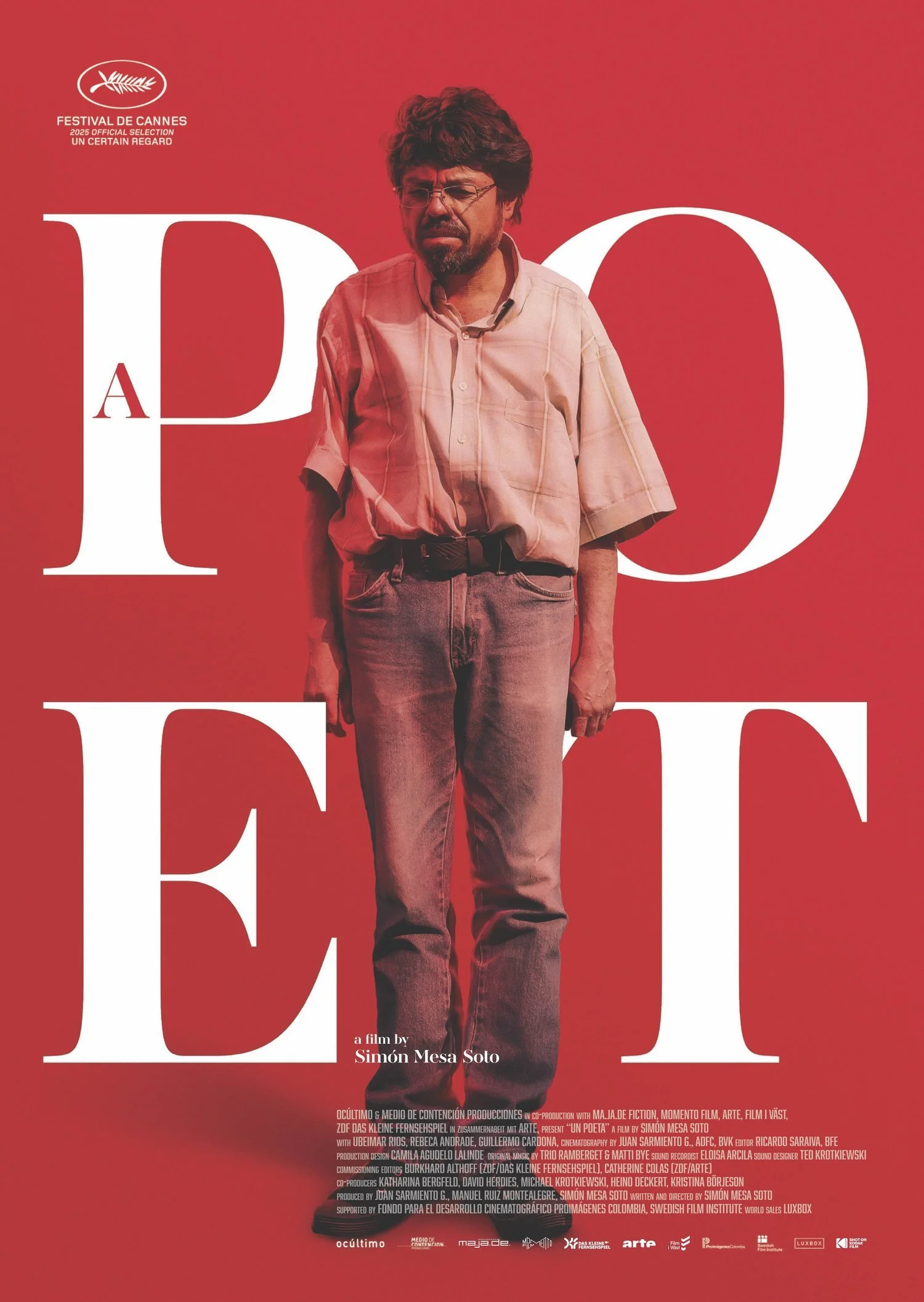

Simón Mesa Soto’s sophomore film, A Poet / Un poeta, is built on exasperated soliloquies that scream for “¡la poesía!” With hilarious yet never cynical humor, it offers a disruptive critique of the art world, unfolding as a theatrical experience that is both comic and deeply uncomfortable. Recently premiered in the Un Certain Regard section of the 78th Cannes Film Festival, Mesa Soto’s film marks a milestone for Colombian cinema—it is only the second Colombian film to compete in that section since José Luis Rugeles’ Alias Maria in 2015.

Born in Medellín in 1986, Simón Mesa Soto has established a strong and fruitful relationship with the Cannes Film Festival. His short film Leidi won the Palme d’Or for Best Short Film in 2014, becoming the first film from Colombia to receive the prestigious award. He returned to the festival’s Official Competition in 2017 with his short Madre, and his 2021 debut feature Amparo had its world premiere in the Critics’ Week section.

Starring Ubeimar Rios, Rebeca Andrade, Guillermo Cardona, Allison Correa, Margarita Soto, and Humberto Restrepo, A Poet follows Óscar Restrepo, a man whose obsession with poetry has brought him neither recognition nor glory. Aging and erratic, he has become a walking cliché—the poet in the shadows. When he meets a humble teenager and begins nurturing her emerging talent, a flicker of light returns to his days. But pulling her into the world of poets may prove to be more curse than calling.

Shot on 16mm, with a camera deliberately wielded as if by an alcoholic person suffering from tremor, hand, A Poet has the trappings of a punk family film. Its slightly dirty image and progressively tightening frame evoke a sense of urgency. Simón Mesa Soto’s tragicomic, melancholy approach lays bare the failings of an embittered yet endearing artist.

After its world premiere at the Debussy Theatre in Cannes, I sat down with Mesa Soto to discuss his visual exploration of poetry, the film’s critique of cultural institutions, and the challenge of cultivating audiences for independent Colombian cinema.

How has A Poet been received at Cannes? And how does it feel to be back at the festival, this time with a feature in Un Certain Regard?

We’re tremendously happy with the warm reception. It’s also a shocking to see how fast this journey has been. We shot the film between January and February, edited it in April, and premiered it in late May. Even so, we’ve remained very calm throughout. We weren’t worried about the result—we were simply grateful for the invitation to the festival.

Being included in Un Certain Regard is especially meaningful for us, given the section’s openness to diverse filmmaking modes and its commitment to looking at cinema from a certain angle. It’s been very fulfilling to see how the film has resonated with its very first audiences.

Were there any particularly insightful reactions from the film’s first audiences?

We premiered at the Debussy Theatre on Monday and have had a couple more screenings throughout the week. We’ve been quite impressed by the variety of cinephiles who genuinely enjoyed the film. It’s interesting that, despite its strong local context, the story is being embraced as a universal one, even though its local context is part of its specificity. Ubeimar, who plays Óscar, has been frequently stopped on the street, receiving kind compliments for his performance. He has clearly generated a lot of empathy for the character—and, more broadly, for the film’s message.

In the midst of its wide-ranging programming, Cannes unfortunately isn’t typically a primary platform for Latin American cinema. How do you see the current landscape?

I feel it is tricky. I don’t always notice many Latin American films at Cannes itself, but I do see those films stand out in other festivals. I’ve always believed that festivals are important launching pads for films, but not their final destination. Every film eventually finds its own space. Of course, Cannes is a major platform in cinema, but I also feel our cinema has been making a significant impact in many other crucial spaces.

In Colombia, despite production challenges, more and more films are being made each year. It has been more difficult due to very limited resources, and there additional circumstances like those in Argentina, where their film institute’s budget has been significantly reduced, if not completely exhausted. This, of course, affects the exhibition of Argentine cinema, which has long been a strong example of how cultural policies shape the films we see across South America.

Lately, I’ve seen many high-quality Latin American films, which are there. Just because they aren’t part of the Cannes selection doesn’t mean they aren’t out there or don’t have an audience.

Would you argue, then, there's been more openness of distribution on those different platforms?

I believe it’s up to us, as filmmakers, both to make the films and to understand our audiences—and that’s quite complicated. A Poet is very much an exercise in that sense: it seeks not only to be an authorial film that is part of a festival. I always had the idea that, of course, a festival like Cannes or San Sebastian or Venice was necessary, but as a platform, not as the film’s final destination. If you make a film only for festivals, you are condemning it to nobody seeing it, to remain printed in the selection.

With A Poet, I constantly kept the audience in mind, without sacrificing its artistic values, but that speaks to the audience in an exercise to try to understand them from the point of view of independent cinema. Of course, this is always uncertain—getting into theaters is very challenging, and we don’t know how it will unfold—but we hope it will be a worthwhile journey.

Making films in Colombia feels a bit like abrir la trocha—“opening the trail,” as they did in the countryside to build small towns. As if we were in constant effort of understanding the terrain. It is up to us to build that unpredictable road. With the rise of streaming platforms, theaters are no longer the dominant market they once were, and that disperses the audience somewhat.

And, with the strengthening of the platforms, now movie theaters are not such a strong market. And there the audience dissipates a little.

Now diving into the film, much of the insight and humor of the screenplay is its ability to comment on expressions of Colombian culture. I'm thinking, for example, of the interplay with the 5,000 and 50,000 bills, the back-and-forth between José Asunción Silva and Gabriel García Márquez, and the influence of foreign embassies on local cultural houses. Could you expand a bit on how you put this together in your screenwriting process?

I think this all came very intuitively during my months of script preparation. Beyond the story itself, these elements you mention reflect my personal concerns as an artist. Ultimately, A Poet is a film about art, and as a filmmaker, I’m always deeply engaged with those questions. When you’re writing a screenplay, you think about a character and you think about a lot of elements that make the story build progressively in your head, contrasted with the bunch of ideas that inspired the story in the first place. And your job is to find its organicity.

A Poet, in short, tells the story of an unemployed man, who lives with his mother, who has a daughter and feels lost and doesn't know what to do with his life. He finds purpose in nurturing a student’s relationship with poetry—and this bond triggers all his conflicts.

I wanted all my dilemmas and concerns to shape the creation of the characters. For me, it felt completely natural. The character of Yurlady, for instance, resembles many of the people I’ve worked with in my previous films, especially the non-professional actresses. Working with non-professional actors relies heavily on the relationship you build with them, which raises ethical questions filmmakers must navigate. Oscar’s relationship with Yurlady as her teacher reflects the kind of bond I strive to build with my actors.That's why I put so much emphasis on the natural way the film came about, because of how organic it feels to my concerns.

That’s why I emphasize how natural and organic the film feels—it emerged from a place deeply connected to my own concerns.

The editing is absolutely fascinating. The cuts perfectly capture the comic tone while accentuate the moments of greater introspection. And on a grand scale, there’s the decision to always show the celluloid frame, explicitly highlighting the film’s materiality. Did you always contemplate editing that way?

For a long time I had the 16mm open gate as a reference in several films, but I don't think it was something that was there from the beginning. Given the speed of the shooting we realized when colorizing it that it existed and that it didn't work against the film. We just wanted A Poet to be dirty and raw. We wanted it to look ugly.

That's where the genuineness of the film's personality comes from.

Exactly. To make it look ugly to incite something else. That's how the film arrives from the lab. We could have cut it or toned it down a bit, but Juan and I decided to just leave it.

The slogan of Medio de Contención—one of the film’s production companies—is #HacerCineConAmigos (#ToMakeCinemaWithFriends). Tell me a bit more about your collaborative process with producer Manuel Ruiz Montealegre and cinematographer Juan Sarmiento G.?

That’s a great way to put it. The three of us are producers on A Poet, but above all, we’re friends. We made Amparo together in 2021—it was the first time that the three of us sat down to think about a film. Juan isn’t a producer, nor am I—we’re just two passionate dreamers of cinema. Him as a photographer and me as a screenwriter-director, we have built a language in our short films together. And in a way we feel it's important to make the decisions of the films. So we became producers ourselves and Manuel is that part of the experience in terms of managing a project and taking the meticulous details.

Friendship has been very important throughout the process. The co-producers in Sweden are also close friends. And I feel that in filmmaking you have to maintain those bonds, you have to relate in the best way, also very sincere. Trust is very important for us.

For that, we surround ourselves with a very valuable and strong team and try to make everything happen in the most beautiful way possible. For this film, I wanted to enjoy the shooting process and soak up all the humor of the script—we laughed a lot. Of course we also faced some very stressful moments because the shoot was was a very tight with a lot of scenes, but we aimed to enjoy it as much as possible. The three of us connected through of our passion for cinema and we see ourselves as dreamers in this titanic task of making a film.

This interview has been translated from Spanish and has been edited for length and clarity.

*Natalia Hernández Moreno is a researcher and Outreach Coordinator for Cinema Tropical – and frequent collaborator for TropicalFRONT.